Luiz Roque is fascinated by the power of images, and specifically by sensations that result from our ability to see. Roque's work covers a broad spectrum of topics, such as the genre of science fiction, the legacy of modernism, the pop culture and “queer politics”. Many similarities are evident in the films: the works have a strong poetic character, combine moments of desperation with optimism and in general the characters cannot be traced back to a specific gender identity. Another clear characteristic is that, in his short stories, Roque often makes use of allegories that possess a considerable degree of elasticity. The artist uses these allegories to reveal the present conflict between technological advances and contemporary micro and macro power structures. In his films Roque combines the nature of science fiction, e.g. equipment that reveals possible images of the future, with imagery from the film world, thus creating scenarios that touch on complex public debates or map out the social tensions that exist in society.

In his film O Novo Monomento (2013), Luiz Roque seems to be responding to the fact that Brazil enjoys presenting itself as a shining example of a successful racial democracy, even though racism is still widespread throughout the country. Moreover, in Brazil there is still little appreciation for the enormous contribution Afro-Brazilians have made to rebuilding Brazil's society. O Novo Monomento is in fact a celebration of the Afro-Brazilian culture and the contribution made by African immigrants. The film starts with an almost ominous citation from an essay written in 1943, Nine Points on Monumentality, which claims that timeless and comprehensive monuments can only be realised in places that have not only a common culture but also a collective consciousness. The onlooker is subsequently taken on a journey to a small, unnamed village in rural Brazil. Poetic black-and-white images bear witness to both the genesis and the celebration of a new monument; dance rituals take place, futuristic elements are combined with traditional African symbols and there no longer seems to be any room for traditional gender relationships.

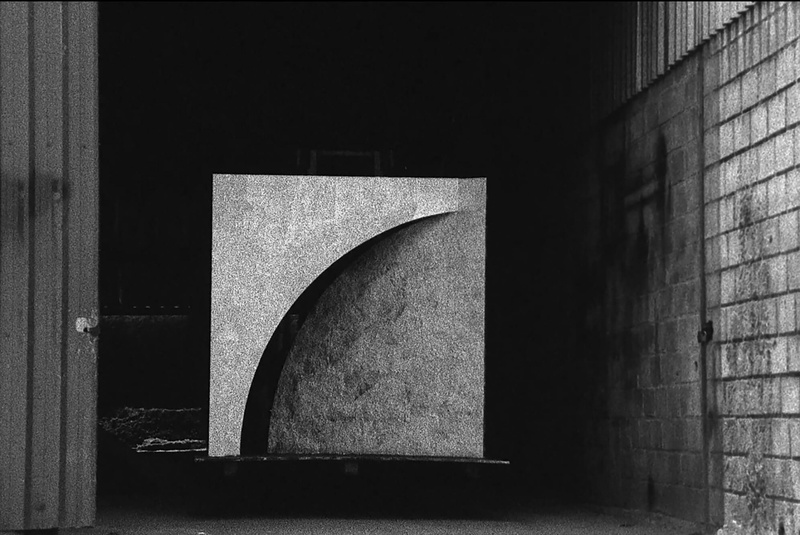

The monument that has been created – based on a famous sculpture of Amilcar de Casto (1920-2002) – one of the best-known Neo-Concretivist artists – is revealed, lifted onto a lorry and then driven off up a mountain into a large empty landscape. The dancers, who accompany the monument on motorbikes, are subsequently revealed as “true crusaders of the idea of unity”. In the film’s last scene we see these same people, but now dancing with other villagers, celebrating the erection of the monument, while probably hoping that they have succeeded in building a timeless and comprehensive monument.